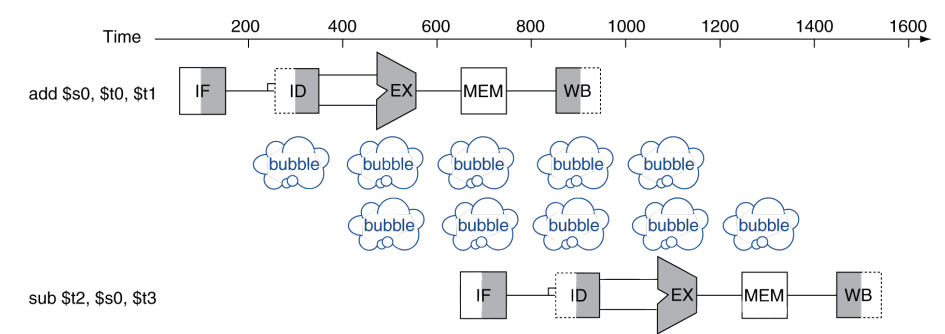

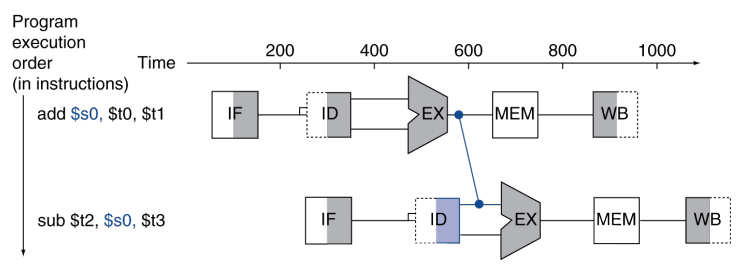

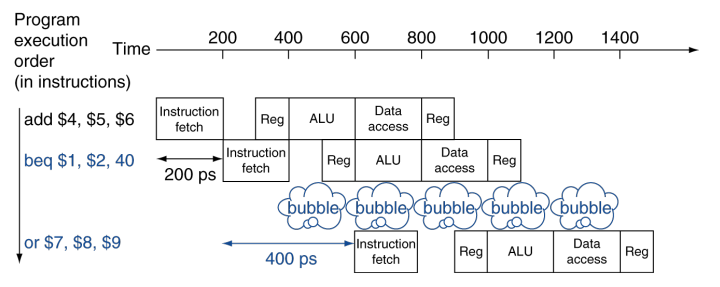

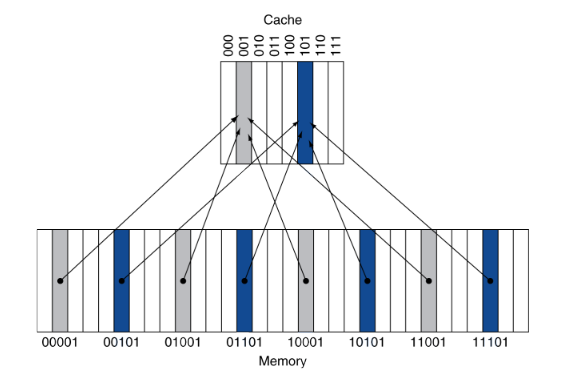

# Pipeline Hazards And Cache --- CS 130 // 2025-11-12 <!--====================================================================--> # Announcements <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Preparing for C programming Installing what you need on your own computer</br> [install guide](../../resources/installing-visual-studio-code) <b>or</b> Set up an account on GitHub and use Codespaces:</br> https://github.com/codespaces <!--=====================================================================--> ## Preparing for Exam 3 * In class on Wednesday, November 19th * You may prepare and use one piece of 8.5"x11" paper with *your* handwritten notes * Check the review exercises posted on Blackboard <!--=====================================================================--> # Review <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--=====================================================================--> ## Review Discussion - what is pipelining? - what is a pipeline hazard? - what are the different types of pipeline hazards? - what are some ways to deal with pipeline hazards? <!--====================================================================--> ## Review: Data Hazards - A **data hazard** occurs when one instruction depends on the result of a previous instruction - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Our example: ```mips add $s0, $t0, $t1 sub $t2, $s0, $t3 ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> What stage does `add` write the result of `$s0` into the register file? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Stage 5: Write Back, *happens at time 5* - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> What stage does `sub` read from `$s0`? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Stage 2: Instruction Decode, *happens at time 3* <!----------------------------------> ## Data Hazards - Would need to stall for two clock cycles in order to wait for the value $s0 to be available for reading  <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - One way to avoid some data hazards without stalling is to **forward** the result to the next instruction immediately when it is available  <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - Forwarding cannot always resolve a data hazard ```mips lw $s0, 20($t1) sub $t2, $s0, $t3 ``` - What stage does `lw` produce the bits of `$s0`? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After Stage 4: MEM <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - Why does this create an unavoidable stall? <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> We cannot send data **backwards in time** <!--====================================================================--> # More on Pipeline Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Data Hazard Exercise * Consider the following MIPS code: ```mips lw $t0, 40($a3) add $t6, $t0, $t2 sw $t6, 40($a3) ``` * Draw timing diagrams showing * how many clock cycles are required when not doing forwarding * how many clock cycles are required with forwarding - show the forwarding lines <!--====================================================================--> ## Rearranging Instructions - Another way to avoid data hazards is by rearranging instructions - Consider the following MIPS code: ```mips lw $t1, 0($t0) lw $t2, 4($t0) add $t3, $t1, $t2 sw $t3, 12($t0) lw $t4, 8($t0) add $t5, $t1, $t4 sw $t5, 16($t0) ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> We need to stall the first add (because it needs `$t2`) - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> We need to stall the second add (because it needs `$t4`) <!----------------------------------> ## Rearranging Instructions - These two stalls could be avoided by rearranging the code in the following way: ```mips lw $t1, 0($t0) lw $t2, 4($t0) lw $t4, 8($t0) add $t3, $t1, $t2 sw $t3, 12($t0) add $t5, $t1, $t4 sw $t5, 16($t0) ``` <!--====================================================================--> # Control Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Control Hazards - A **control hazard** (aka branching hazard) is when the next instruction to be executed is not yet known - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Caused by **branching** instructions such as `beq` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> During a `beq` instruction, at what pipeline stage do we know which branch will be taken? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After Stage 3: EX <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - One way to avoid control hazards is by stalling  - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After every branch statement, we stall for one cycle <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - The pros of the "always stall" approach are: 1. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Simple and easy to understand 2. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Will always work - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> The con of "always stall" is: + It is slow <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - An alternative to the always stall approach is **branch prediction** + Make an educated guess on what the next instruction will be and execute that + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> If incorrectly guessed, "undo" the steps and go to the correct branch <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - **Static branch prediction** will always predict a certain branch depending on the branching behavior + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Predict forward branches not taken + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Predict backward branches taken (loops) - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Dynamic branch prediction** keeps track of how many times a branch is taken and updates its predictions based on history <!--====================================================================--> # Pipelined CPU Design <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipelined Control Complete <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/pipelined_control_complete.png' height='550'> <!--====================================================================--> ### Pipelined Architecture with Hazard Detection and Forwarding <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/pipelined_architecture_with_forwarding.png' height='550'> <!--====================================================================--> # Caches <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Memory Organization - When a program uses memory, it tends to use it in *predictable ways* - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> As a result, it is possible to speed up memory usage dramatically by creating a **memory hierarchy** + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Register file is small but it's ridiculously fast + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> SRAM is larger but slower + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> DRAM is larger still but even slower + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Hard disks are HUGE but also the slowest <!--====================================================================--> ## Terminology - **Cache:** + An auxiliary memory from which high-speed retrieval is possible - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Block:** + A minimum unit of information that can either be present or not present in the cache - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Hit:** + CPU finds what it is looking for in the cache - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Miss:** + CPU doesn't find what it's looking for in the cache <!--====================================================================--> ## Designing a Cache - Having a hierarchy of memories to speed up our computations is great, but we also face several design challenges - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> If we are looking for a value in memory address `x`, how do we know if it is already in the cache? <!--====================================================================--> ## Direct Mapped Cache - One idea is to use a **direct mapped cache** where the address `$x_n$` tells us where to look in the cache - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> If there are `n` slots in the cache, then we look for `x` in the `x % n` index of the cache <!----------------------------------> ## Direct Mapped Cache  <!----------------------------------> ## Direct Mapped Cache - If the number of blocks in the cache is `$n = 2^k$`, then `(x % n)` is simply the last `k` bits of `x` + Makes it extremely efficient to find where a block is in the cache - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Since multiple blocks may have the same index in the cache, how do we know if the block of memory there is the one we're looking for? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Include a **tag** that uniquely identifies the block <!----------------------------------> ## Direct Mapped Cache - Some parts of the cache can be empty and/or underutilized if their index, by chance, doesn't pop up as often - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> How can we improve utilization? <!--====================================================================--> ## Fully Associative Cache - The "extreme" alternative to direct mapped caching is **fully associative** caching + Any block can be stored in *any* index of the cache --- - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Advantage**: Every spot in the cache will be used, and therefore less cache misses will occur - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Disadvantage**: We need to search the entire cache every time, so the hit time will increase <!--====================================================================--> ## Set-Associative Cache - The compromise between these approaches is the **set-associative** cache + Blocks are *grouped* into sets of `n` blocks + Block number determines which set - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Still requires searching through all `n` blocks in a set - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Can be tuned to have a decent balance between hit rate and hit time <!--====================================================================--> <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/cache_comparisons.png' > <!--====================================================================--> ## Handling a Cache Miss 1. Check the cache for a memory address + Results in a miss 2. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Fetch corresponding block from RAM or disk + Wait for block to be retrieved (stall) + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Write block to cache 3. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Continue pipeline (unstall) <!----------------------------------> <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/handling_cache_misses.png' height='500'> **Exercise:** show what happens if the next three memory access are to addresses 10110, 00000, and 10111 <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> <!--====================================================================--> ## Multilevel Caches - Usually, caches are implemented in multiple "levels" for maximal efficiency + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> L1 is smallest/fastest + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> L2 is larger/slower + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> L3 is largest/slowest - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Modern multi-core processors typically have dedicated L1 and L2 caches for each core and a shared L3 cache