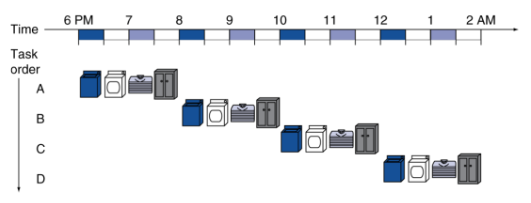

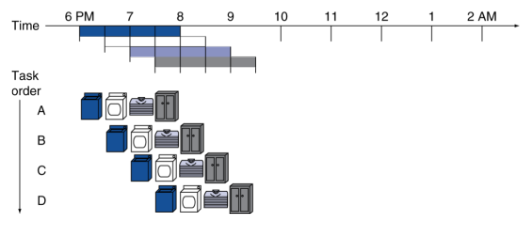

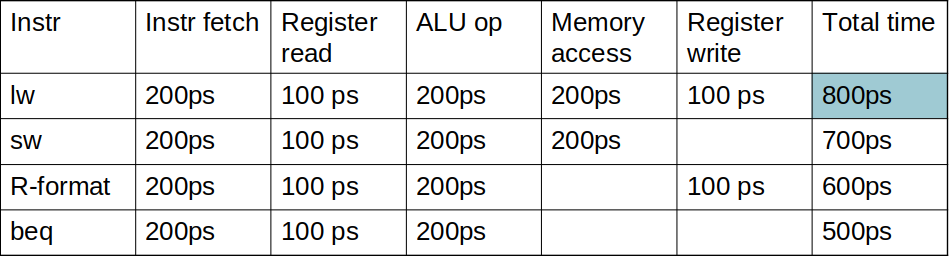

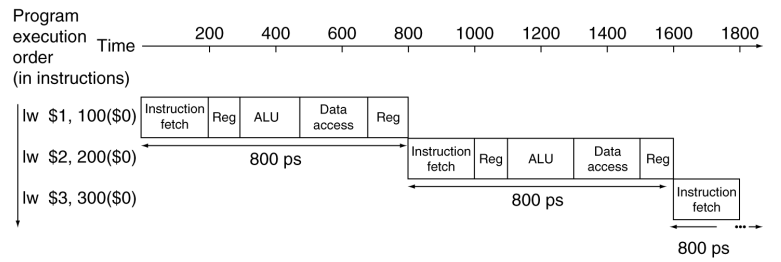

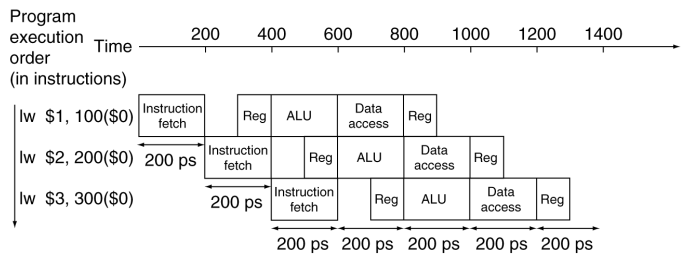

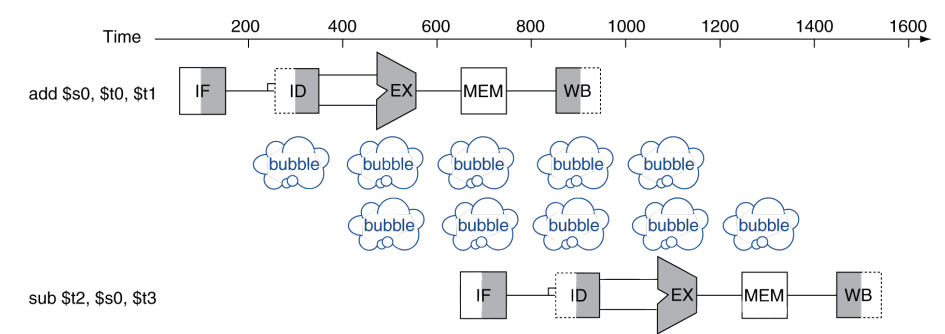

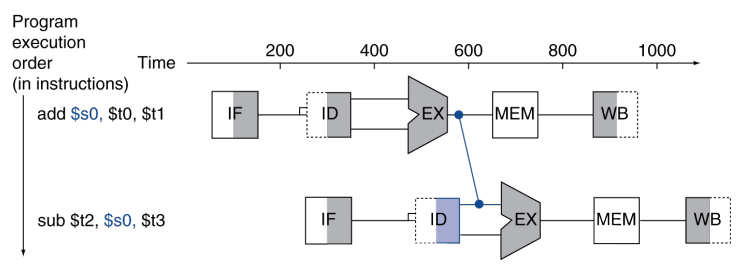

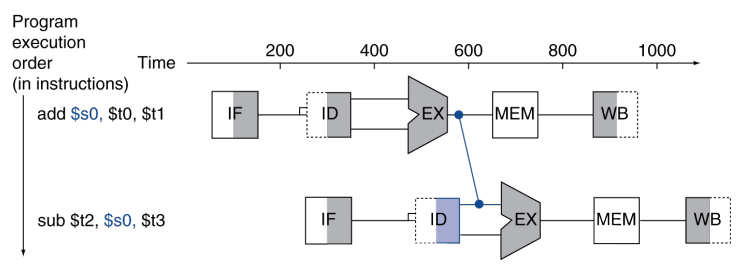

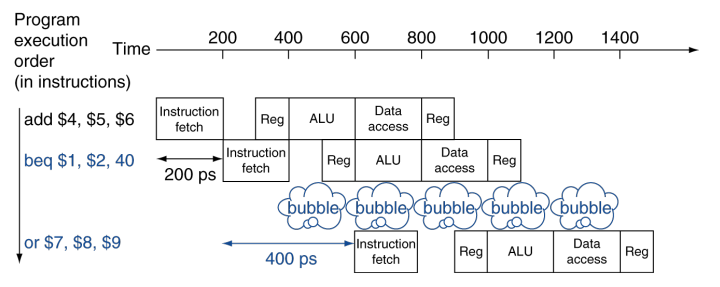

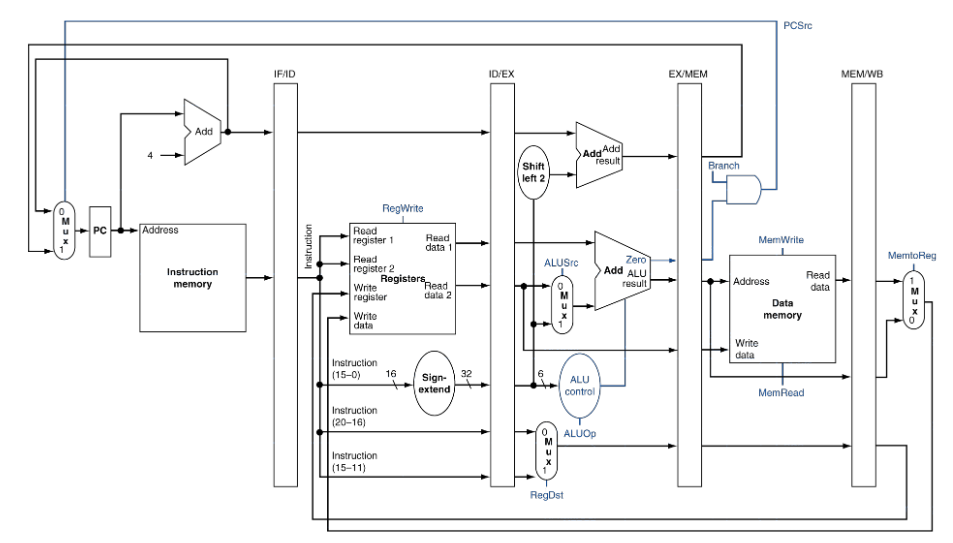

# Pipelining --- CS 130 // 2025-11-10 <!--====================================================================--> ## Preparing for C programming Installing what you need on your own computer</br> [install guide](../../resources/installing-visual-studio-code) <b>or</b> Set up an account on GitHub and use Codespaces:</br> https://github.com/codespaces <!--====================================================================--> ## Suggestions on using the RAM unit in your assignment <div class="twocolumn-alt"> <div> <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/logisim_RAM.png' width='700'> </div> <div> * Use 32 bit data width * Use 16 bit address width, but only use some of the bits coming out of the ALU </div> <!--=====================================================================--> # Review <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ```mips beq $8, $9, 5 #jump ahead 5 instructions ``` 000100 01000 01001 0000000000000101 <div class="twocolumn-alt"> <div> <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/datapath_with_control_annotated.png' width='900'> </div> <div> ALUop: "sub"</br> ALUSrc: 0</br> Branch: 1</br> MemRead: 0</br> MemWrite: 0</br> MemtoReg: x</br> RegWrite: 0</br> RegDst: x </div> </div> <!--====================================================================--> # Performance Issues <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Performance Issues - Longest delay determines clock period - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Some stages of the datapath are idle waiting for others to finish - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Can improve performance by **pipelining** <!--====================================================================--> # Pipelining <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--=====================================================================--> #### Breaking down instruction execution - Five stages: 1. **IF**: Instruction Fetch - read it from instruction memory 2. **ID**: Instruction Decode and Register Read - split instruction into parts, read register data 3. **EX**: Execute - ALU calculates result 4. **MEM**: Memory Access - read from or write to memory 5. **WB**: Write back - put new data back into a register <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipeline Analogy - Suppose you need to do four loads of laundry - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Each load of laundry needs to be 1. Washed via the washing machine 2. Dried via the dryer 3. Folded 4. Put away in the closet - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> For simplicity, assume that each task takes 30 mins <!----------------------------------> ## Pipeline Analogy - How long does it take to complete four loads? - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> One approach uses only one stage at a time and does nothing in parallel:  - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Notice that the washer is unused 3/4 of the time <!----------------------------------> ## Pipeline Analogy - Another approach is harnessing parallelism by running independent stages simultaneously  - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> How much of a speedup does this approach give us? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> $8/3.5 = 2.3\times$ speedup + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> $2n/0.5n = 4\times$ speedup if running continuously <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipelined Datapath <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/piplined_datapath.png' height='550'> <!----------------------------------> ## Pipelined Datapath - Five stages: 1. **IF**: Instruction Fetch 2. **ID**: Instruction Decode 3. **EX**: Execute 4. **MEM**: Memory access 5. **WB**: Write back <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipeline Performance - Assume time for stages is: + `$100\text{ps}$` for register read/write + `$200\text{ps}$` for other stages <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> <!----------------------------------> ## Without a Pipeline  - Why must the clock be set to `$800\text{ps}$` when some instructions like `beq` could be completed in `$500\text{ps}$`? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Clock speed is limited by **slowest** instruction: `lw` <!----------------------------------> ## With a Pipeline  - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> How much of a speedup does this approach give us? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> `$2400/1400 = 1.7\times$` speedup + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> `$800n/200n = 4\times$` if running continuously <!----------------------------------> ## Pipeline Performance - Does using a pipeline increase the efficiency of executing **individual** instructions? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> No, it slows them down from `$800\text{ps}$` to `$1000\text{ps}$` + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Performance benefits come from increased **throughput** due to the parallelism <!--====================================================================--> ## Why MIPS is Good for Pipelining - All MIPS instructions are the **same length** + Easy to fetch instruction in cycle 1 + Easy to decode instruction in cycle 2 - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> MIPS has only **a few instruction formats** + Registers will always be in same location + Easy to decode instructions <!--====================================================================--> # Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Hazards - Up until now, we have pretended that each instruction is **independent** of the others and that there are no conflicts - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> In reality, instructions often depends on previous ones, which may cause naive pipelining to fail <!----------------------------------> ### Exercise ```mips add $s0, $t0, $t1 sub $t2, $s0, $t3 ``` - What stage does `add` write the result of `$s0` into the register file? - What stage does `sub` read from `$s0`? - Why is this a problem? - Can you think of any ways to fix this? <!--====================================================================--> ## Types of Hazards - Situations that prevent immediately executing the next instruction in the pipeline are called **hazards** - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Three types of hazards: 1. Structure hazards 2. Data hazards 3. Control hazards <!--====================================================================--> # Structure Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Structure Hazards - In our laundry example, we were assuming the "fold" and "put away" stages could be done simultaneously + However, if you are working by yourself, you would have to do them sequentially - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> A **structure hazard** occurs when a required resource is busy performing another task <!----------------------------------> ## Structure Hazards - Recall that our MIPS pipeline has five stages: + IF, ID, EX, MEM, WB - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> The ID and WB stages read and write to the register file simultaneously + Does this create a structure hazard? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> No, by design, the register file supports simultaneous reading and writing <!----------------------------------> ## Structure Hazards - Suppose that we stored instruction memory and data memory in the same location + Would this create a structure hazard? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Yes, the IF and the MEM stages would need to simultaneously read from the same memory + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> If using a single memory, the pipeline would need to **stall** to wait for the resource to become available <!--====================================================================--> # Data Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Data Hazards - A **data hazard** occurs when one instruction depends on the result of a previous instruction - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Our example: ```mips add $s0, $t0, $t1 sub $t2, $s0, $t3 ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> What stage does `add` write the result of `$s0` into the register file? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Stage 5: Write Back - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> What stage does `sub` read from `$s0`? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Stage 2: Instruction Decode <!----------------------------------> ## Data Hazards - Would need to stall for two clock cycles in order to wait for the value $s0 to be available for reading  <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - One way to avoid some data hazards without stalling is to **forward** the result to the next instruction immediately when it is available  <!----------------------------------> ### Discuss: What does this look like on the datapath? <div class="twocolumn"> <div>  <!-- .element width="400px" --> </div> <div> <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/datapath_with_control.png' width='500'> </div> </div> <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - Can you think of a situation where forwarding cannot resolve a data hazard? ```mips lw $s0, 20($t1) sub $t2, $s0, $t3 ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> What stage does `lw` produce the bits of `$s0`? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After Stage 4: MEM <!----------------------------------> ## Forwarding (aka Bypassing) - Why does this create an unavoidable stall? <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> We cannot send data **backwards in time** <!--====================================================================--> ## Data Hazard Exercise - Consider the following MIPS code: ```mips lw $t0, 40($a3) add $t6, $t0, $t2 sw $t6, 40($a3) ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Assuming there is no forwarding implemented, are any stalls necessary? - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> How many clock cycles are required to execute these three lines of code without forwarding? <!----------------------------------> ## Data Hazard Exercise - Consider the following MIPS code: ```mips lw $t0, 40($a3) add $t6, $t0, $t2 sw $t6, 40($a3) ``` - Assuming there IS forwarding implemented, are any stalls necessary? - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> How many clock cycles are required to execute these three lines of code with forwarding? <!--====================================================================--> ## Rearranging Instructions - Another way to avoid data hazards is by rearranging instructions - Consider the following MIPS code: ```mips lw $t1, 0($t0) lw $t2, 4($t0) add $t3, $t1, $t2 sw $t3, 12($t0) lw $t4, 8($t0) add $t5, $t1, $t4 sw $t5, 16($t0) ``` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Identify any stalls that are necessary even with forwarding and hazard detection active <!----------------------------------> ## Rearranging Instructions - These two stalls could be avoided by rearranging the code in the following way: ```mips lw $t1, 0($t0) lw $t2, 4($t0) lw $t4, 8($t0) add $t3, $t1, $t2 sw $t3, 12($t0) add $t5, $t1, $t4 sw $t5, 16($t0) ``` <!--====================================================================--> # Control Hazards <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Control Hazards - A **control hazard** (aka branching hazard) is when the next instruction to be executed is not yet known - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Caused by **branching** instructions such as `beq` - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> During a `beq` instruction, at what pipeline stage do we know which branch will be taken? + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After Stage 3: EX <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - One way to avoid control hazards is by stalling  - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> After every branch statement, we stall for one cycle <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - The pros of the "always stall" approach are: 1. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Simple and easy to understand 2. <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Will always work - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> The con of "always stall" is: + It is slow <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - An alternative to the always stall approach is **branch prediction** + Make an educated guess on what the next instruction will be and execute that + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> If incorrectly guessed, "undo" the steps and go to the correct branch <!----------------------------------> ## Control Hazards - **Static branch prediction** will always predict a certain branch depending on the branching behavior + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Predict forward branches not taken + <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> Predict backward branches taken (loops) - <!-- .element: class="fragment"--> **Dynamic branch prediction** keeps track of how many times a branch is taken and updates its predictions based on history <!--====================================================================--> # Pipelined Datapath Design <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipelined Datapath Design <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/piplined_datapath.png' height='550'> <!----------------------------------> ## Using Registers (Has Bug) <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/pipelined_datapath_with_registers.png' height='500'> <!----------------------------------> ## Using Registers (Bug Fixed) <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/pipelined_datapath_fixed.png' height='500'> <!--====================================================================--> # Pipelined Control <!-- .slide: data-background="#004477" --> <!--====================================================================--> ## Pipelined Control Simplified  <!----------------------------------> ## Pipelined Control Registers - Control signals derived from instruction and passed through the relevant registers  <!----------------------------------> ## Pipelined Control Complete <img src='/Fall2025/CS130/assets/images/COD/pipelined_control_complete.png' height='550'>